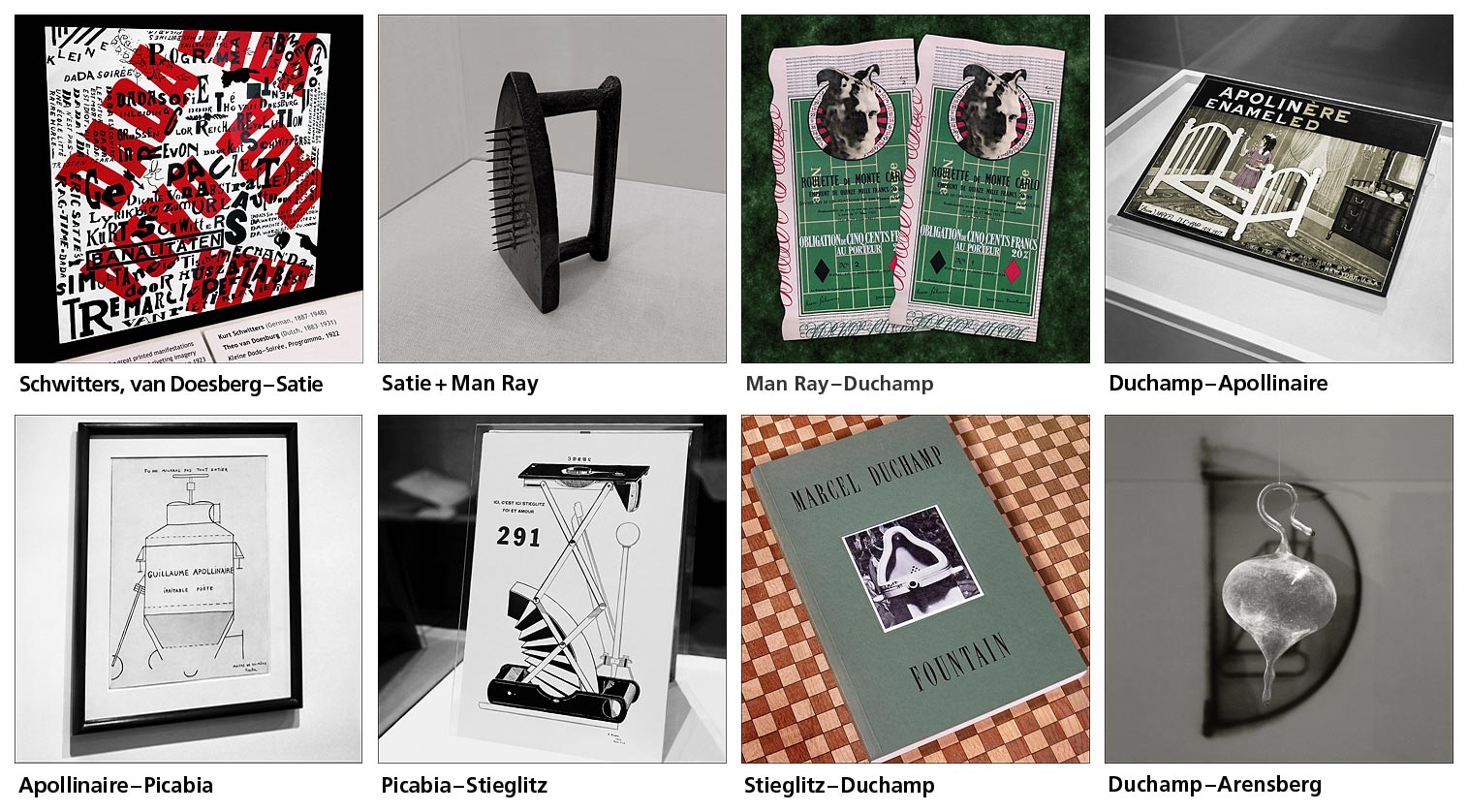

Kurt

Schwitters, Theo van Doesburg — Eric

Satie Eric Satie + Man Ray Man Ray + Marcel Duchamp Marcel Duchamp — Guillaume Apollinaire Guillaume Apollinaire — Francis Picabia Francis Picabia — Alfred Stieglitz Alfred Stieglitz — Marcel Duchamp Marcel Duchamp — Walter Arensberg |

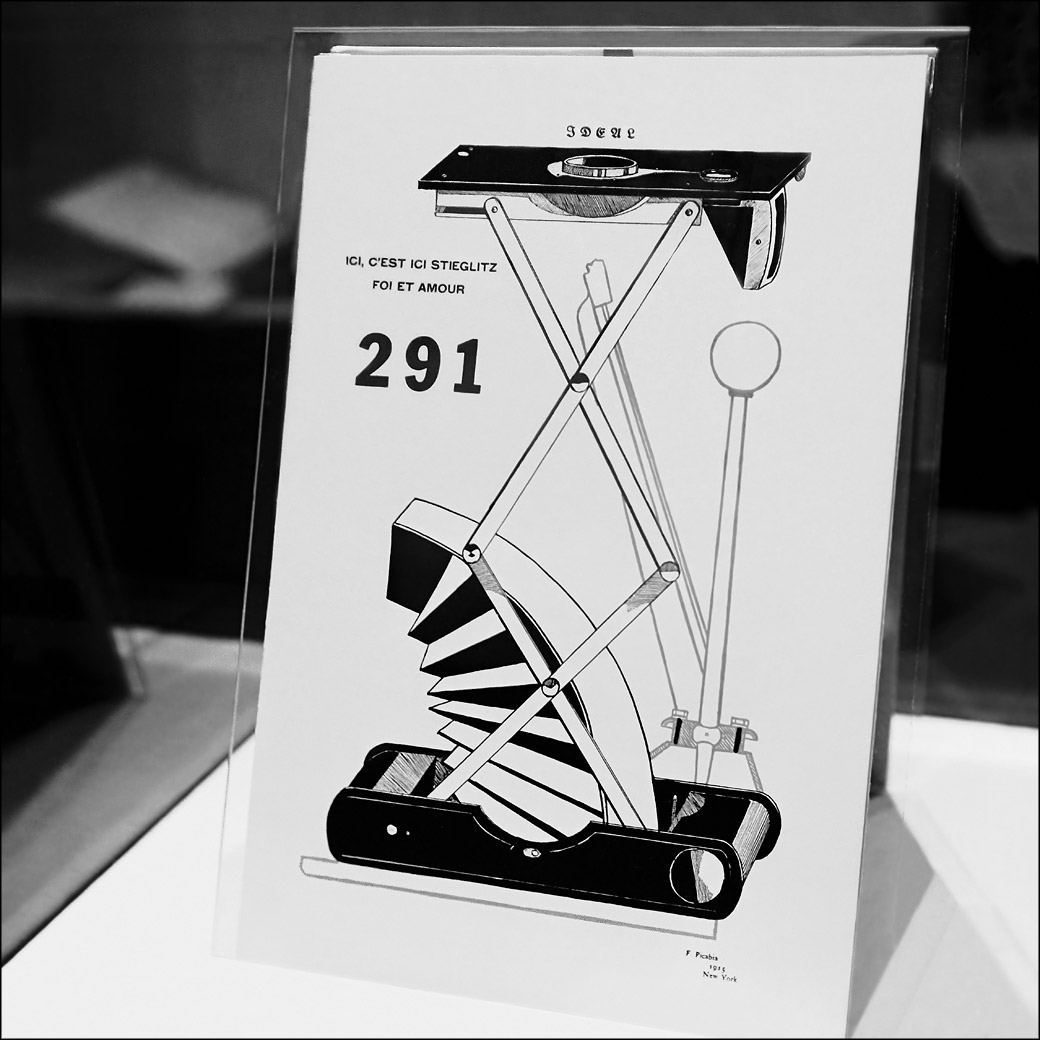

| This set of eight photographs of artworks forms a sequence of references. One artist referring to another, who then refers to another and so on, so as to present a chain of artists’ connections and relationships. |

1924

sustained a return to what the politicians called “normalcy,” six

years after the period of social upheaval that followed the devastation

of the First World War and the 1918 flu pandemic. The Dada artists

had responded to the era with novel, nonsensical artworks, sometimes

political sometimes not, sometimes humorous sometimes not, reflecting

the craziness and uncertainty of the time, advancing what was even

thought

possible

in a work of

art. This way of thinking and working may be relevant again today

for an artist who wants to express a personal vision in difficult

times. |

|

| Program

and poster for Kleine Dada Soirée, 1922 Kurt Schwitters and Theo van Doesburg Erik Satie playing “Rag-time Dada” Dada hurts. Dada does not jest, for the reason that it was experienced by revolutionary men and not by philistines who demand that art be a decoration for the mendacity of their own emotions… I am firmly convinced that all art will become dadaistic in the course of time, because from Dada proceeds the perpetual urge for its renovation.“ |

— Richard Huelsenbeck, “Dada

Lives,” 1936 |

|

| Cadeau (Gift), Man Ray, assisted by Erik Satie, 1921 In his autobiography Man Ray recounted the story of the making of the original Cadeau: “On the day of the opening of his first solo exhibition in Paris he had a drink with the composer Erik Satie and on leaving the café saw a hardware store. There with Satie’s help—Man Ray spoke only poor French at this point—he bought the iron, some glue and some nails, and went to the gallery where he made the object on the spot. He intended his friends to draw lots for the work, called Cadeau, but the piece was stolen during the course of the afternoon.” |

— Jennifer Mundy, “Notes

from The Tate, London,” 2003 |

|

| Monte

Carlo Bond, Marcel Duchamp, photograph of Duchamp by Man Ray, 1924 Extracts from the Company Statutes Clause No. 1. The aims of the company are: 1. Exploitation of roulette in Monte Carlo under the following conditions: 2. Exploitation of Trente-et-Quarante and other mines on the Cote Azur, as may be decided by the Board of Directors. Clause No. 2. The annual income is derived from a cumulative system which is experimentally based on one hundred thousand rolls of the ball; the system is the exclusive property of the Board of Directors. The application of this system to simple chance is such that a dividend of 20% is allowed. Clause No. 3. The Company shall be entitled, should the shareholders so declare, to buy back all or part of the shares issued, not later than one month after the date of the decision. Clause No. 4. Payment of dividends shall take place on March 1 each year or on a twice yearly basis, in accordance with the wishes of the shareholders. |

— From

the back of the bond as translated by Arturo Schwarz |

|

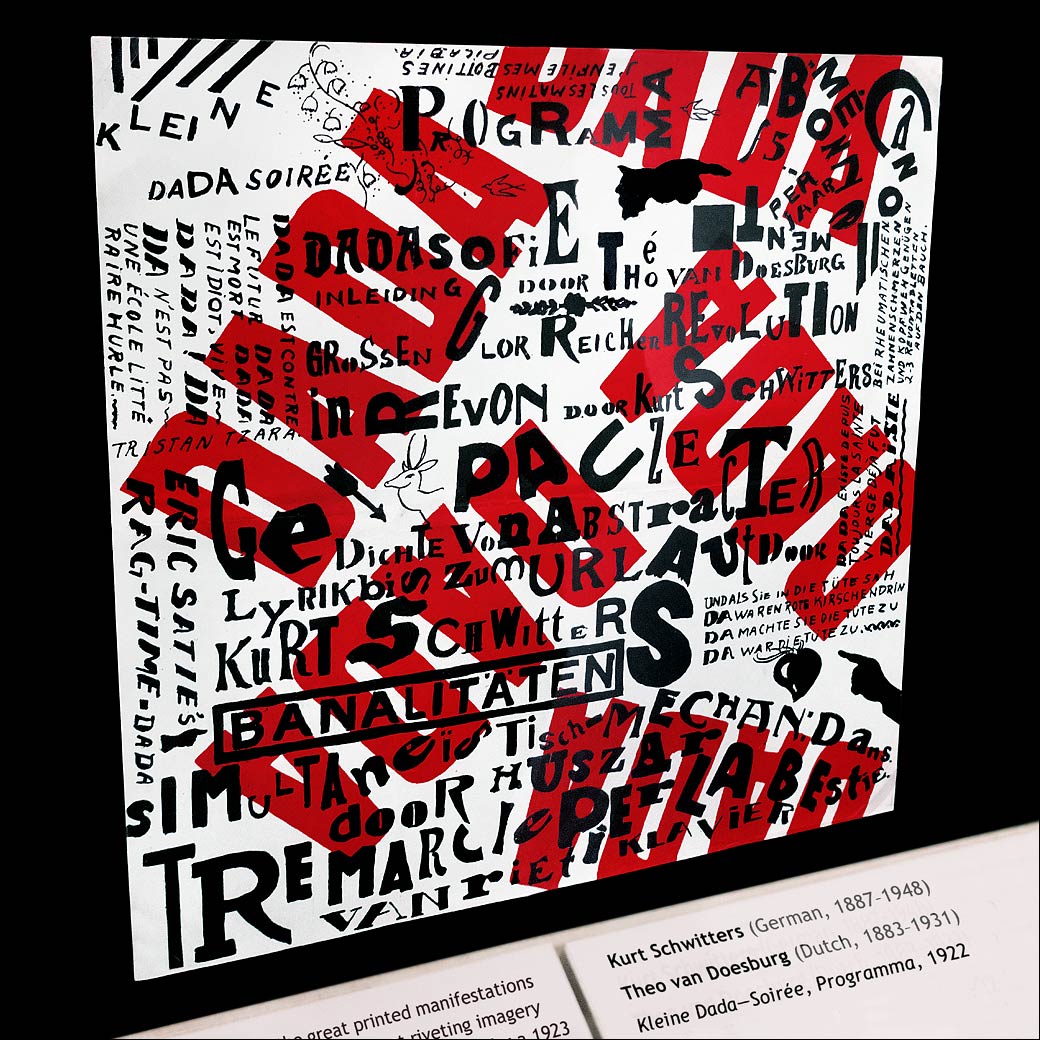

Fountain, Marcel

Duchamp (William Camfield, author, 1989), cover photograph by Alfred

Stieglitz,

1917, with Marsden Hartley’s The Warriors, 1913,

as background. Here placerd on an infinite chessboard. Duchamp saw the artist as a readymade to be moved through the market like a chess piece on a grid.” |

— David Joselit, Société Anonyme:

Modernism for America, 2006 |

|

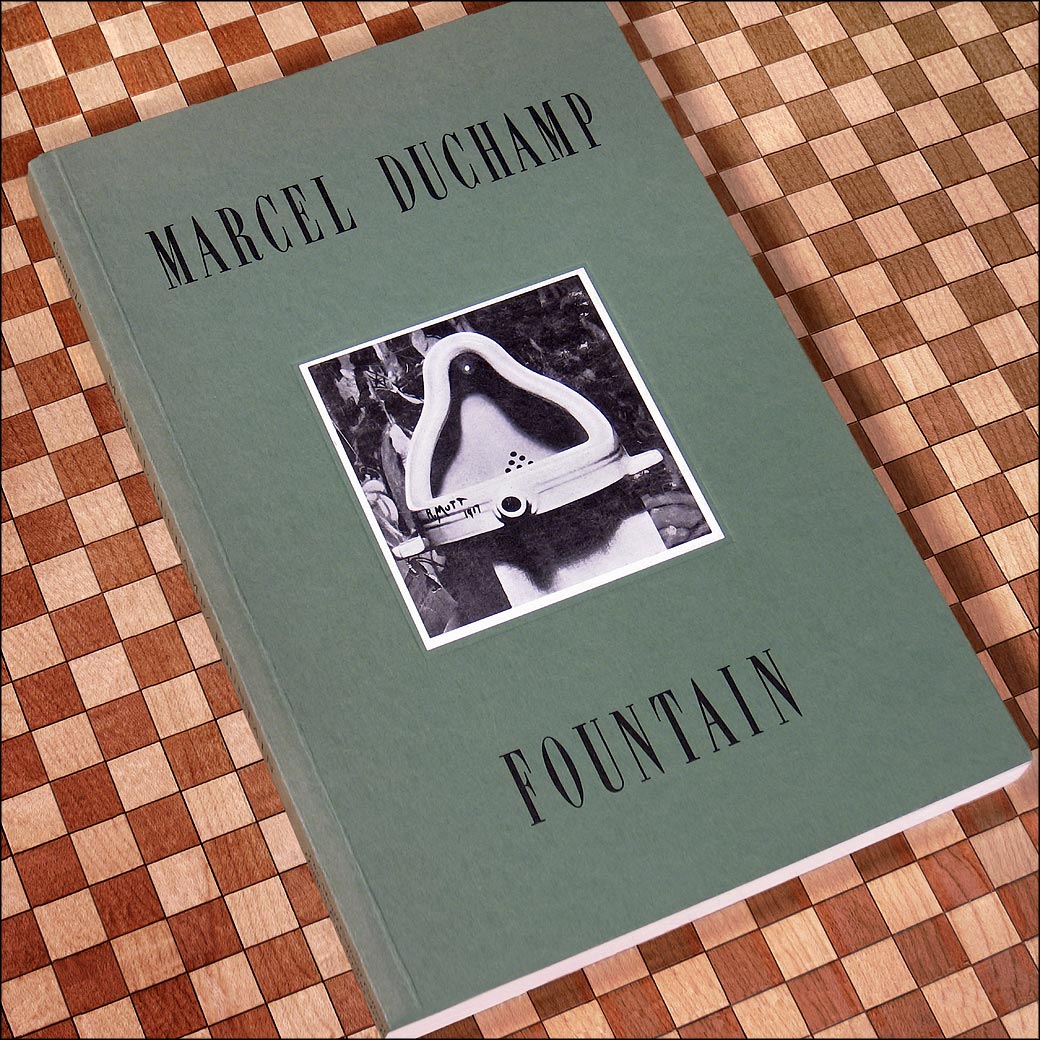

C'est

Ici Stieglitz Foi et Amour (This is Stieglitz / Faith and Love, |

— Paul Haviland, “291” magazine,

1915 |

|

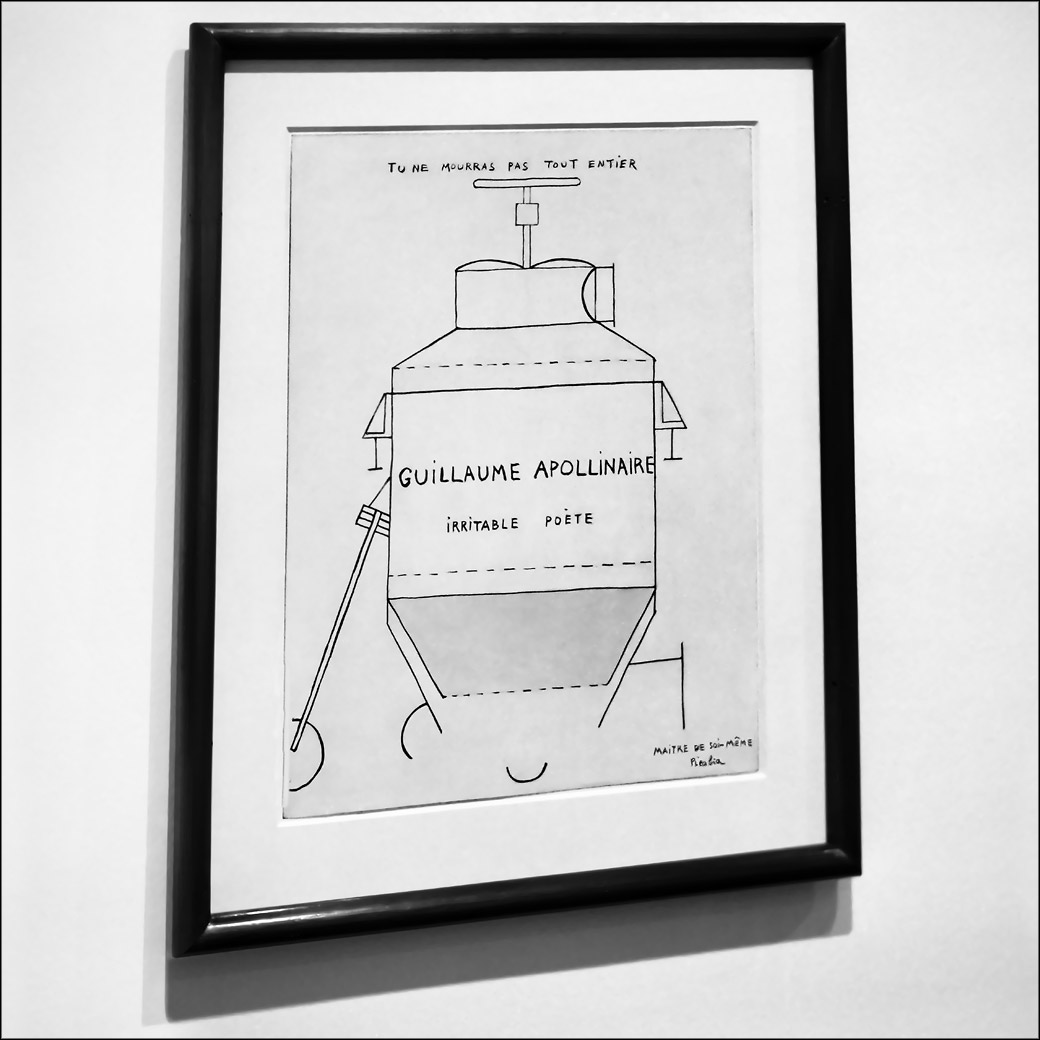

Guillaume

Apollinaire,

Irritable Poète, |

— The

character Dr. Cornelius Hans Peter from Apollinaire’s novel, Que Faire, 1900 |

|

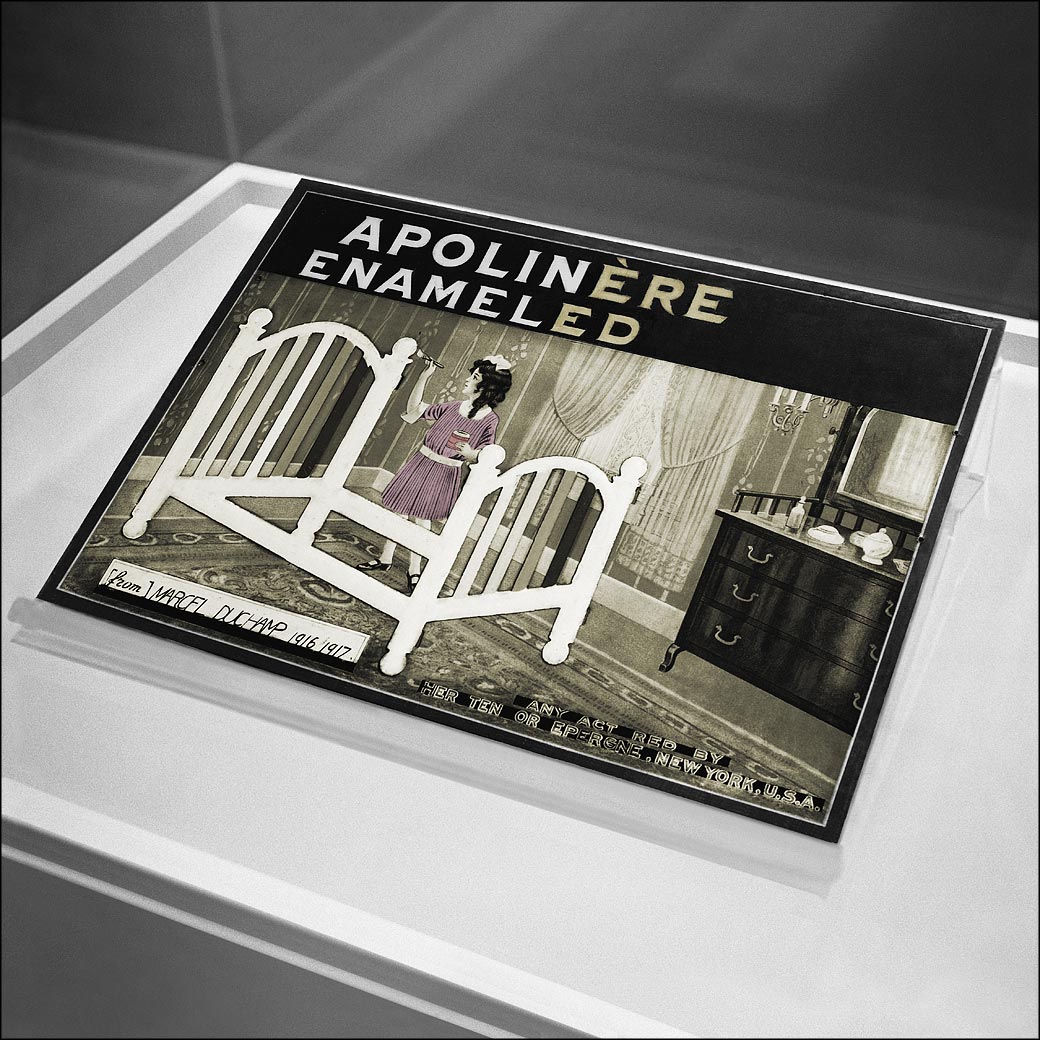

Apolinère

Enameled, Marcel Duchamp, 1916, |

— Pablo

Picasso, Juan Gris, Max Jacob, Paul Dermée, Reverdy & Blaise Cendrars, at a banquet to honor Guillaume Apollinaire, 1917 |

|

| 50ccs

of Paris Air, Marcel

Duchamp, 1919, a gift to Walter Arensberg In the background: Glider Containing a Water Mill in Neighboring Metals, Duchamp's first artwork on glass, 1913–15 Duchamp purchased this “empty” ampoule from a pharmacist in Paris as a souvenir for his close friend and patron, Walter C. Arensberg. A vial with nothing in it may be the most insubstantial “work of art” imaginable. From a molecular point of view, air is not considered nothing, but when displayed so carefully in an art museum it seems to be less than one might expect. Its precise meaning was rendered even more unstable in 1949, when the ampoule was accidentally broken and repaired, thus begging the question: Is the air even from Paris anymore? |

—Curator’s

label, Philadelphia Art Museum, 2006 |

| All photographs of artworks by Victor Landweber |