| |

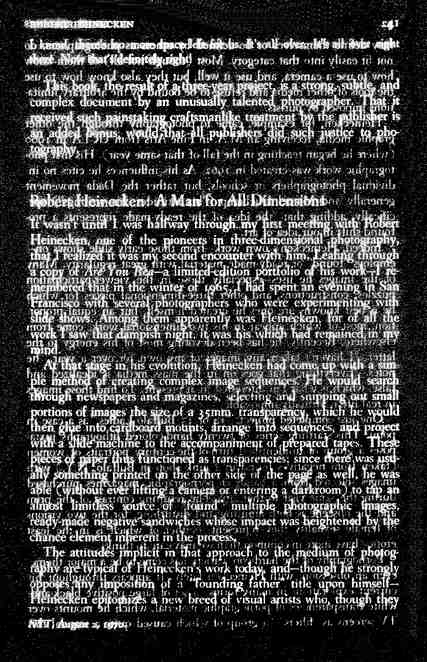

I first saw Are You Rea in 1972 when it arrived in Rochester at

a little photobook store called Light Impressions — a storefront

that seemed about 4×8 feet with a counter and a small exhibition

area with room for a half dozen prints to hang in a row above a display

rack containing the novelty items we called photobooks. Among the inventory

at the time: Les Krims' little portfolios; Lustrum Press' greatest hits;

the Canadian magazine Image Nation; mostly softcover fun, self-published

stuff.

As that time, mail-order

book sales were the main thrust of Light Impressions' business, and

their hope was to develop a mailing list that would allow them to open

up a vast market for what we all felt was going to be a massive revolution

in photobook publishing as well as a large revolution in art. (We may

note that a revolution has occurred, but it is not the one we had expected).

It is hard to imagine where else a publication such as Are You Rea

might have appeared, and at first glance I embraced it like a co-conspirator.

Are You Rea

was not a book at all, but more of a "guerilla" portfolio,

a "multiple" (as cheap artists' editions were sometimes called).

It certainly was something, but what…? A bunch of prints? pages?

photograms? page-o-prints? magazine-o-grams? Heineckenographs? If it

had a model at all, it was one of the Institute of Design portfolios

which had been very experimental, printed in various ways with a variety

of materials. The ID portfolios were mostly photographic, very modest

productions designed for the people who made them, which was a good

idea because no one else was interested. "Photography" was

what one saw at its best in Life magazine, at its worst in one's

own family album. Even the photographs of Aaron Siskind and Harry Callahan,

included in the ID portfolios, had no commercial value. Although 1970

is usually regarded as a turning point for photography; after some conspicuous,

lively auctions and a range of other activities, a market suddenly showed

up.

Clearly, whatever

else Are You Rea may have been, it was also the result of a printmaking

process: photo offset; ink on paper. Inexpensive and accessible, photo-offset

lithography could allow the small press or self-publisher to get out

work that otherwise could not have been commercially justified. Contrary

to modern assumptions, desktop publishing really began with the liberation

of printing; even mimeograph is desktop publishing, isn't it? And wasn't

the 1947 Stieglitz memorial portfolio also a pack of cheap reproductions,

never to be confused with the photographer's original fine prints? Are

You Rea was a portfolio, and it was cheap, so I bought it.

Thus did I meet

up with this curious and distinctive little portfolio, the diminutive

size of which gives no indication of its status as a first-rate cultural

event. It immediately fell into place with what I already knew about

Heinecken and his art since I had met him two years earlier at a workshop

at the Center of the Eye in Aspen, Colorado. I had hung a show of his

work at a gallery there and remember several things: 1) that Heinecken

had hair longer than my own, indicating a seriousness of counter-cultural

stance over a comparatively longer period of time; 2) that he was the

guy who went on an outing to a Minor White shrine just outside of Aspen,

called The Grottos, armed not with a Kodak but with a Kodak girl —

a full size, cardboard representation of, in this case, a youthful and

scantily clad Cybill Shepherd that could be placed strategically within

what was otherwise only a picturesque landscape; 3) that the colors

of pork chop printed on (allegedly black-and-white) printing-out paper

were simply not be be believed.

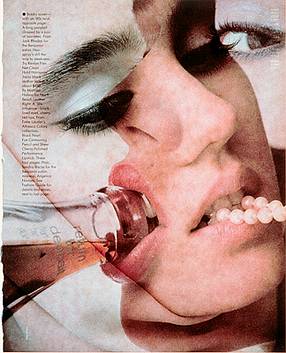

Heinecken is a guerilla

artist inspired more by the surrealism of Andre Breton than the politics

of Karl Marx. Take, for example, his surrealist joke of altering a magazine

and then putting it back on the magazine rack. As a guerilla "attack,"

this is pretty mild stuff (we imagine John or Jane Doe's shock and smile).

As art it is a much stronger assault because it attacks sensibility.

While the Vietnam war was grinding on under Nixon's ironic peace initiative,

I remember an extended, day-long debate on another topic with graduate

students, let by an important critic, which was not surprisingly eclipsed

by one of Heinecken's magazine pages recently arrived by mail: a Revlon

beauty overprinted with a smiling young soldier proudly displaying two

severed heads; a sense of being on fire, "signaling through the

flames," as Artaud put it; the contradiction of American-sponsored

violence and the glossy magazine landscape of feminine beauty, all nicely

sexy and so-o-o delicious and so very expensive. Similarly, if one expects

to see a photograph when looking at Are You Rea, the simultaneous

overlay of two images defeats the expectation of seeing with the eye

and shocks one into seeing instead with the mind. We perceive a superficial

substrate, the surface of the paper, a thin stratum shared by the images

on either side of the page. Deprived of a camera's "view,"

we are nonetheless asked to "see," to answer the question:

"Are you rea_? (fill in the blank).

It is an obvious

truism that any page of any magazine can stand for the totality of this

culture because every page is, literally, a piece of the culture. It

is not of the culture of about the culture, but is

the culture itself. Pornography is not only something to be found in

the old man's locked desk, brought out for a frolic in fantasyland,

but is readily available in fact and in spirit, a key indicator of culturally

sanctioned behaviors. Pornography, and the prostitution it implies,

addresses the culture's total representation of women in commercial

media and the limited range of acknowledgeable possibilities within

sexual relationships. Heinecken deals with such charged material on

a physical level, both in regard to his own body's response to a latent

pornographic subject and by the use of actual, ink-on-paper magazine

pages as original negatives.

Heinecken has always

seen what he was doing as art: not knowledge; not truth or politics;

not anything else but art. Because these are offset lithographs of photograms

made from lithographs of photographs, I found myself more interested

in the idea underlying the gesture of their making than in their delicacy

of tone, the quality of their craft, or even the pictures themselves.

The pictorial structure was photographic but cameraless which, as it

seemed to Moholy Nagy, was a more fundamental, hence more direct, way

of working, of getting to know one's materials so one could, in good

Bauhaus fashion, begin the work with and through and in terms of the

materials themselves.

Are You Rea

is printed but is not comprised of "prints," yet it is an

original edition — not reproductions. Its pictures are not carefully

crafted objects that call attention to their own physicality but are

the things themselves, and that is how they call attention to their

making, their idea, because their materiality is, in a sense,

nothing as compared to the carefully crafted silver-gelatin prints of

the high West Coast tradition of Weston, Adams, and White. It was precisely

such an assault on the artful photographic print-making tradition that

was the point of a cheap offset edition: an anti-elitist, democratic

art of action; a paroy of the deluxe-edition portfolios of the past;

a counter-cultural thrust away from the unique (and expensive) to the

mass-printed "multiple." (Who could have dreamed that the

project would be revisited for precisely opposite reasons only two decades

later? But who could have begun to imagine what two decades would and

wouldn't bring to art and photography and to Robert Heinecken).

My reading of Are

You Rea was from a viewpoint increasingly critical about the whole

notion of documentary photography, that the photograph has a privileged

relationship to the real, especially the "real" of social

change. Heinecken was against photojournalism and the conventions of

documentary photography as he was against the Newhall-endorsed, West

Coast, craft-based tradition of Weston and Adams. His playing field

was in the ball game of conceptual art, grounded in the minor league

of photography (sequed into printmaking), with major-league ambition

like some other West Coast players (Baldessari, Huebler, Irwin, Kaprow,

Ruscha, etc.).

What I got, I think,

was this: I saw the gesture and absorbed it and worked with it immediately.

In these photograms of odd pages from who knows what source, I hardly

even looked at the "pictures" in any sense of connoisseurship

or even with any interest in a formal, physical, surface analysis. I

understood the portfolio in a glance; it was as if made for me. I knew

exactly what it was: it freed me to work. And that was a great gift.

|